Order and Progress

In the The Accidental President, a memoir by Brazil’s former president, Fernando Henrique Cardoso, there is a passage on the origin of the country’s national motto, “Order and Progress” (Ordem e Progresso).

Before solving this mystery, I should mention I have no idea what the US national motto is, or even if we have one. I know Brazil has a national motto because it’s printed on every flag.

According to Wikipedia, printing a motto on a flag is quite rare. In fact, Brazil’s may be the only one. Some Arab nations have “God is Allah” on their flags, but I don’t know if that qualifies as a national motto.

The US certainly has no motto or printing on its flag, although “In God We Trust” is on every currency. If that’s the US motto, it’s not a bad one, but it seems a bit misplaced. I understand Saudi Arabia putting God on its flag, but the US was founded on the principle of the separation of Church and State.

“E Pluribus Unum” (Out of many, one) also appears on American money, so maybe that’s the US motto. I imagine a good motto for the US would be, “One for all and all for hot dogs.”

If “Out of many, one” is the US motto, I’d say that’s even lamer than “In God We Trust” because who speaks Latin anymore. Trusting God seems self-fulfilling, self-evident, and redundant, like when Jewish texts refer to the Jews as the chosen people. It’s fine for any religion to talk about God, but once those sayings go on your flag or your money, you force everyone else to get onboard. It alters the delivery.

In November 1889, three army officers entered the palace of Brazil's emperor, Dom Pedro II, and presented a message ordering him and his family to leave, to which Dom Pedro replied, “I am leaving, and I am leaving now.” The emperor made the prudent choice as the palace was surrounded by soldiers eager to depose him. There is a famous lithograph depicting the delivery of this message that threw Dom Pedro into exile. The painting shows the three officers who delivered the message to Dom Pedro. One of them was Fernando Cardoso's grandfather, Joaquim Ignácio Batista Cardoso.

The country’s founding fathers didn’t waste time placing “Order and Progress” on the first flag of independence, along with 21 stars in imitation of the US flag, with each star representing a state. The name chosen for the new country was the Republic of the United States of Brazil.

Finding the customs or history of a foreign country confusing doesn't take much effort, and I'd been wondering about “order and progress” since I first glimpsed the flag. Interestingly, no one I met here seemed to know the origin of the phrase. Besides Brazil’s unique idea of placing a motto on its flag, in my mind order and progress are opposites. Order implies stability and maintaining the status quo, keeping peace by honoring the old values. Progress involves leaving the old ways behind to adopt new traditions. Progress signifies embracing the new to be better prepared for the future. To make progress, society must engage with the future, which involves the acceptance of change, the opposite of maintaining the status quo.

One Brazilian professor I queried told me, “Brazil’s motto is ironic; I can’t see any order or progress these days.” Rather than losing sleep over a nation’s motto, in Brazil or the US, I had filed away the motto mystery while wondering if the founding fathers had purposefully insisted on an ironic motto.

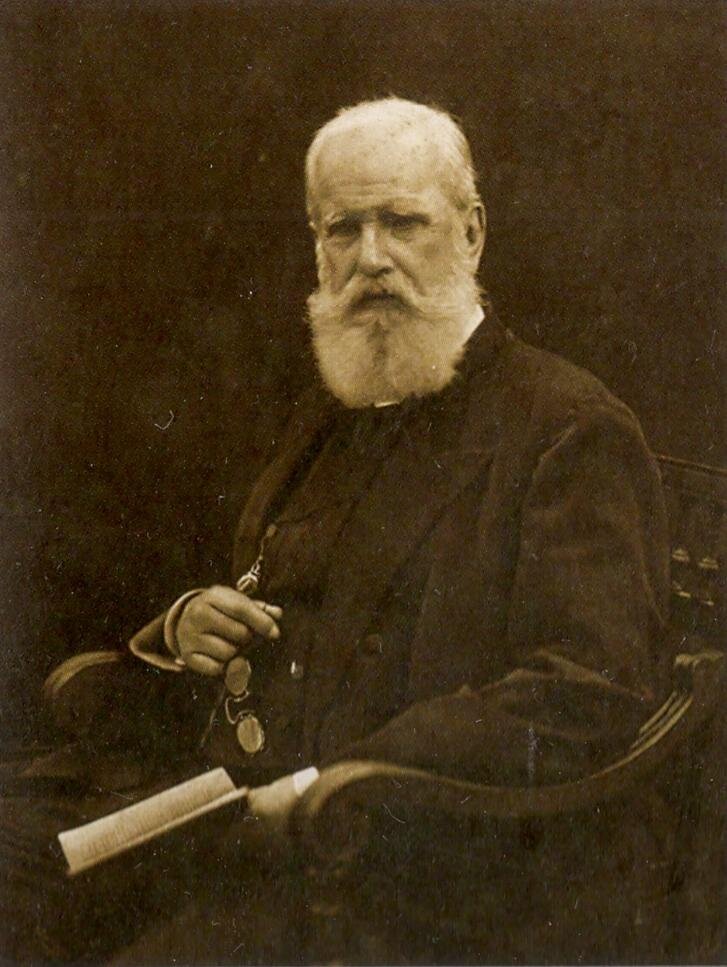

Brazil’s former president Fernando Henrique Cardoso.

Then I read Cardoso’s memoir with the description of his revolutionary grandfather, and I discovered that the pairing of order and progress is not only not a contradiction, but the phrase is not even a Brazilian invention. In fact, it's derived from Auguste Comte, the 19th-century French philosopher who founded the doctrine of Positivism, which places facts and truth as the ultimate goals of civilization and became the overriding political philosophy of 19th century Europe and the US. Comte believed that in our search for truth, humans should progressively learn more, which leads society to continually advance in the positive sense of the word. Comte is often referred to as the first philosopher of science.

In the 19th century, Rio de Janeiro was the capital of Brazil. Its residents thought of Rio as the Paris of South America. For example, when it came to studying a foreign language, people learned French not English. At that time, the military schools in Brazil were teaching the principles of Comte’s Positivism. Thus, it’s no surprise that the military officers who orchestrated the departure of Dom Pedro in 1889 were believers in Positivism. Historians have concluded the motto comes from one sentence of Comte’s that summarizes his doctrine of Positivism: “L’amour pour principe et l’ordre pour base; le progrès pour but” (Love as a principle and order as the basis; progress as the goal).

If a French philosopher could find a way to fit order and progress into the same doctrine nor less the same sentence, that’s good enough for me. By instilling order within society in a loving way, Comte saw progress as a natural social outcome or at least the goal of society.

It makes sense the gentlemen orchestrating a bloodless revolution to overthrow a monarchy are going to consider the emperor’s departure as a sign of progress. The revolutionaries who deposed Dom Pedro were acutely aware of the social and economic inequality posed by a monarchy. Additionally, the exile of the country’s figurehead could be cause for political chaos in which case the call for order is a wise choice.

The military who deposed the emperor wanted the rule of law and order to prevail in Brazil, but they also sought a more educated populace that would lead to a less hierarchical society and progress, as expressed in Comte’s doctrine. They believed passionately in the construction of a strong, centralized state that exists for the benefit of the country. In the 19th century, much of the power of Brazil was concentrated in the hands of a small number of wealthy landowners, particularly in the states of São Paulo and Minas Gerais. With the departure of the emperor, the first military police were organized as a way of maintaining order. No one expected the wealthy oligarchs to accept a government seeking more economic equality. In 1889, only landowners were permitted to vote, which meant fewer than three percent of the Brazilian population was eligible. Not even a third of adults knew how to read at that time.

Left to right: Oscar Niemeyer, Joaquim Cardoso and Paulo Werneck

The wealthy weren’t the only ones eager to disrupt order. In 1894 just five years after the establishment of the Republic, Joaquim Cardoso (remember the officer in the painting) was called to the state of Rio Grande do Sul to help suppress a bloody civil war. A rebel army of 3000 men had plans to march on São Paulo but were eventually defeated. Coincidentally, Joaquim took his orders in Rio Grande do Sul from General Manoel do Nascimento Vargas, whose son Getúlio would later become president of Brazil.

Much order and progress has transpired in the last hundred years, along with some of the inevitable disorder and failure. Today, Brazil is living through a time of radical transformation, but at least the civil wars have passed. The old myths by which Brazilians oriented themselves are disappearing. The future depends on who will rise to lead the country.