A Nation of Yogis

If you think your headstand is in good shape, try making it your casual comportment. Brazilians are everyday yogis.

I was in a supermarket one afternoon when a torrential downpour erupted. Rain is commonplace in Curitiba, a large city in Brazil that gets more rain than Seattle, but this deluge was impressive for its suddenness. Additionally, the supermarket had a tin roof, providing the rain with an overpowering vocal expression. I needed to raise my voice to talk to my wife.

A few minutes later the power went out, eliciting a mass exclamation from the store's patrons. Luckily the front of the supermarket was framed in large glass windows, and it was the middle of the day so we weren't thrust into cavernous darkness. Nevertheless, I froze. My hands creased with sweat clenching the shopping cart, imagining mayhem. I braced for the worst. My wife stands less than five feet tall; she might be crushed in the chaos of shopping carts full of epicurean delights rushing for the free exit.

With one arm I encircled her, assuming the silence following the initial exclaims was the calm before the storm. I waited. Nothing. Instead of pandemonium, people continued shopping.

Brazilians don't panic. They expect unexpected turns in the road. Their definition of an emergency is different from yours and mine. They never raise their voices in public. Their kids dash madly around restaurants without parental admonishment as waiters carrying trays of food deftly navigating around them.

People are more patient here, enduring a lifetime of waiting on lines. It's not yoga for health but species continuity. Darwin smiles down on Brazil – survival favors the flexible. Fortitude is essential in a developing country. It's a trait so ingrained it's probably genetic by now.

Brazilians aren't taken aback when on Monday morning, driving to work, they discover their normal route is impassable because over the weekend the city has changed a street from two-way to one-way.

Yielding, like a tree in a storm, is an essential survival technique in this world. Brazilians have low expectations. They count on little from social services or infrastructure, thanks to the endemic corruption that leaves the government perpetually broke. In other words, people expect less from their government and they get it.

There is no cross-country highway system. All elementary and secondary schools operate on a split-session schedule to double the capacity of the buildings. There are no passenger trains; even India has a train system. Planes don't depart from the gate listed on the boarding pass. Concerts don't start on time nor do TV shows.

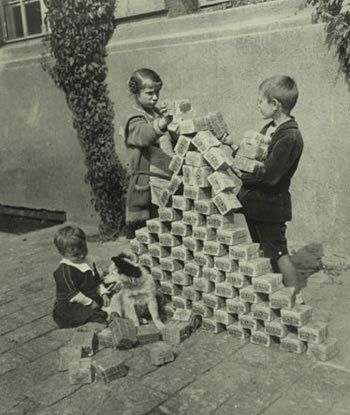

Children playing with money in Weimar Germany

Lax timing and weak infrastructure aren't the only potholes requiring elasticity. The population endured two decades of military dictatorship, which was followed by hyperinflation that hit 3,000 percent annually and continued for a decade. During that time, the government introduced seven currency changes.

As the expat community in Curitiba is minute, I'm not exaggerating to suggest I was the only foreigner in the supermarket that day, which means I was probably the only person who had never experienced a supermarket blackout. I didn't know the protocol. Hence, I took cues from my Brazilian wife who showed no panic and felt my arm squeezed around her as nothing more than the open affection typical here.

Watching Brazilians go about their food shopping without electricity, I imagined Americans coping with the name of dollars changed to something else; or 100 percent inflation per month; or supermarket shelves without peanut butter.

It's inevitable to feel powerless in a country crippled by bureaucratic nonsense, but Brazilians have mastered the art of perseverance. They don't expect events to start on time or chores like returning an item to a store to be simple. They're so good at tolerating confusion and finding an alternative route there's a term for it, the jeitinho brasileiro (Brazilian way). Perhaps that explains how happiness has become inbred as well.

Brazilians endure and maintain their composure and are satisfied in a fashion that is impossible for Americans to imagine. To suggest to an American that he is not in control of his life is terrifying, it's Kafkaesque.

In my sanguine moments, I imagine Brazilians' excessive contentment is linked to affection. There's a lot of hugging and kissing. Young mothers breastfeeding in public is commonplace; is there anything more comforting? If tree-huggers can save forests, what can people huggers save?

As my wife and I finished our darkened shopping trip, we gingerly approached the check-out lane expecting a long wait. Instead, technology had triumphed, and the digital cash registers were operating off a back-up generator, which was keeping the freezers viable.

The teenage girl at the cash register nonchalantly negotiated our purchases. As a second girl bagged the groceries and placed them into our shopping cart, she warned us the elevators to the parking garage weren't working. She then pushed our cart out of the store for us all the way to the side entrance ramp to the garage. As we followed her, we passed the frozen elevators, and I saw a clerk handing a cup of water to an outstretched arm in the elevator. A middle-aged woman stuck inside alone wasn't in a panic, she was thirsty.